Chinook Salmon Abundance

Credit: CDFW

California Chinook salmon hatch in rivers and streams and migrate as juveniles to the Pacific Ocean. After three to four years, they return as adults to the same freshwater body to spawn and die. Salmon “runs” are named for the season when adult fish return to their freshwater habitat. Human activity maintains salmon runs in the Sacramento River through hatcheries and dam releases. In contrast, relatively minor human influences on the Salmon River allow scientists to better assess how climate change may be impacting salmon in their freshwater habitat. For more information, download the Chinook Salmon Abundance chapter.

What does this indicator show?

Salmon River Spring-run Chinook Salmon Abundance

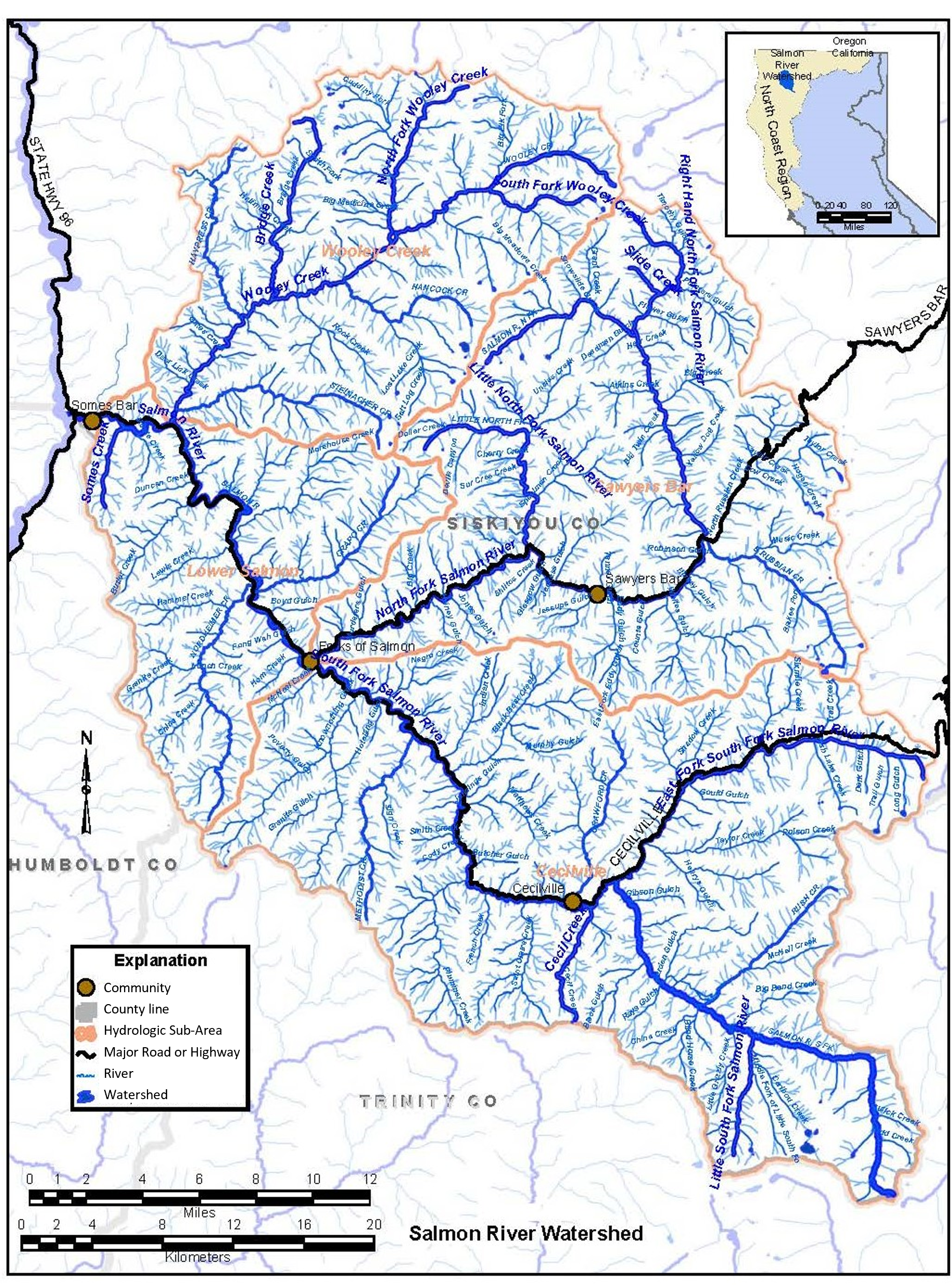

The graph shows numbers of salmon returning to their spawning grounds in the Salmon River. Fish are counted in the upper mainstem and at the north, south and east forks of the river (shown in map below) on a single day in late July.

- Salmon River spring-run Chinook salmon abundance has fluctuated between 1990 and 2024, averaging about 600 fish each year. For seven consecutive years since 2017, salmon counts were far below average, ranging from 95 to 290.

- In the Sacramento River, salmon abundance has fluctuated considerably over the past four decades. Of the four Chinook salmon runs in this river (fall-, late-fall-, winter- and spring), the winter-run has seen periods of alarmingly low numbers. Mining, water diversions, and other activities have historically threatened Sacramento River Chinook. Climate-related disturbances have further stressed salmon populations in recent decades.

The Salmon River in northern California has the largest remaining wild spring-run Chinook salmon in the Klamath River watershed (map). Adult salmon migrate upstream from the ocean in late spring/early summer. Spring-run salmon in this region were declared threatened by the State of California in 2022.

Credit: USGS

Why is this indicator important?

- Salmon are among California’s most valued natural resources, given their economic and ecological importance. The fish are valued both as a food source and as a species of cultural significance by California Tribes.

- Salmon can serve as an indicator of the health of both marine and freshwater ecosystems. Their populations reflect conditions in both ecosystems, such as prey availability in the ocean, and temperature and stream flow in rivers.

- Fishery managers rely on estimates of salmon returns to spawning grounds to gauge fish abundance and make informed decisions about sustainable fish management practices.

- Marine mammals, larger fish, and sea birds feed on salmon. In rivers and streams where adults die after spawning, salmon carcasses cycle nutrients their bodies have accumulated from the ocean.

What factors influence this indicator?

- Warmer air temperatures and declining snowpack reduce the amount of snowmelt that provides cold water year-round to salmon freshwater habitats. Increasing water temperatures and decreasing river and stream flows can negatively impact salmon spawning, egg viability, juvenile growing conditions, and migration. The Sacramento River winter-run salmon is uniquely vulnerable to these impacts since the fish spawn during the hot summer months.

- Warming Salmon River temperatures threaten the survival of juvenile spring-run salmon that live in the river throughout the summer. Because the river has no dams or hatcheries, little infrastructure and minimal water diversions, increasing water temperatures are likely due to climate influences.

- Warm ocean temperatures can alter the marine food web by changing the distribution of salmon predators, competitors, and prey species. Acidifying ocean waters may impact squid, crabs and krill that are important to the salmon diet.

As part of a plan to save the winter-run Chinook salmon, juvenile fish (left) are reintroduced to their historical spawning and rearing habitat at high elevations that have been blocked for decades by the Shasta Dam (right).

Credit: Steve Martarano, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (left); DWR (right)

Additional resources

- California Department of Fish and Wildlife, California Central Valley Chinook Population Database Report

- California Current Integrated Ecosystem Assessment, California Current Ecosystem Status Reports

- Pacific Fishery Management Council, Salmon Management Documents

- Salmon River Restoration Council, Fisheries Program

- The Nature Conservancy, State of Salmon in California